Table of Contents

EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION

Sarah Kiernan and Claire Anscomb

Read online | Download Pdf

THE DREAMWORK OF LANGUAGE: DONALD DAVIDSON BETWEEN METAPHOR AND MEANING

Alessandro Cavazzana

Read online | Download Pdf

AN INSTITUTIONAL THEORY OF ART CATEGORIES

Kiyohiro Sen * Winner of Debates in Aesthetics Essay Prize 2022 *

Read online | Download Pdf

IS LAKOFF ARNHEIMIAN

Ian Verstegen

Read online | Download Pdf

TRUST, POETIC APPROPRIATION AND POETIC GHOSTS: AN INTERVIEW WITH RALPH WEBB

Rebecca Wallbank

Read online | Download Pdf

LOOKING THROUGH IMAGES: A PHENOMENOLOGY OF VISUAL MEDIA, BY EMMANUEL ALLOA

Fotini Charalabidou

Read online | Download Pdf

INTRODUCTION

Sarah Kiernan and Claire Anscomb

↑ Back to top ↑

It is our great pleasure to introduce the 2022 general issue of Debates in Aesthetics (DiA). In this issue there are three original articles, two of which examine issues related to metaphor as understood by Donald Davidson (Cavazzana) and Conceptual Metaphor Theorists and Gestalt Psychologists (Verstegen), while another examines how appreciative behaviour comes to be associated with different categories of art (Sen). There is also an interview with poet Ralf Webb, where he discusses his debut collection Rotten Days in Late Summer and the relationship between authors and readers (Wallbank), and a review of the recently published ‘Looking Through Images: A Phenomenology of Visual Media’ examining how Emanuel Alloa answers the question “what is an image?” (Charalabidou).

In ‘The Dreamwork of Language’, Alessandro Cavazzana offers a fresh approach to Donald Davidson’s 1978 paper What Metaphors Mean. Davidson’s rejection of metaphorical meaning is illuminated, Cavazzana suggests, by placing it within the broader theoretical framework of Davidson’s philosophy of language. He argues that Davidson’s proposal that metaphors do not have any special cognitive content distinct from their literal meaning can be better understood by sufficiently considering Davidson’s distinction between the semantic and pragmatic aspects of language (2022, 15). The central claim here is that the imaginative visions and associations that are stimulated by metaphors are solely the result or domain of the way in which language is used rather than any inherent meaning of language. This conclusion clearly rests on a particular definition of ‘meaning’ and, as Cavazzana explains, this definition originates from a linguistic theory in which meaning and truth are intimately connected. This, of course, is truth-conditional semantics – the position that the “conditions under which a sentence would be true is a way of indicating the meaning of that sentence” (2022, 17). This leads Cavazzana to note the influence of Alfred Tarski’s theory of truth on Davidson’s semantics and explain how Davidson believes that Tarski’s equivocation of truth biconditionals with linguistic meaning can be applied to natural languages as well as formal languages if they are modified to include the context of utterance (2022, 19).

Metaphors seem to present the gravest challenge for the application of truth-conditional semantics to natural languages but, according to Cavazzana, Davidson addresses this challenge by appealing to the inclusion of the context of utterance and construing metaphors as the ultimate examples in which this context takes effect. In short, it is the truth conditions that give a sentence its meaning (not whether or not those conditions are met), and in the case of metaphors where truth conditions are certainly not met, the obvious falseness of the statement leads the listener to look for some other purpose for its utterance. Thus, the allegorical ‘meaning’ of metaphors is solely derived from the context in which they are used and metaphors cannot be said to possess any special cognitive content beyond the literal, according to this theory of language. Cavazzana writes that his assessment of Davidson’s paper differs from analyses which fail to sufficiently consider Davidson’s views on semantics or align his treatment of metaphors with his wider work on the theory of meaning (2022, 14). Such a treatment shows that Davidson’s views are in fact consistent and that his work on metaphors is in no way incongruent with his wider work on semantics.

Sen starts his article by recounting Kendall Walton’s famous argument that there are correct categories for artworks and that the correct appreciation of artworks is based on such categories (2022, 32). As Sen outlines, while Walton offered some factors that count towards it being correct to perceive a work in a particular category, such as which category the artist intended or expected the work to be perceived in, none of these seem to provide necessary or sufficient conditions and nor is it clear how categories originate. Acknowledging the difficulties in addressing the membership question (what determines the correct category of a work?) Sen proposes a more fruitful line of enquiry is to focus on the behavioural question: how are the correct appreciative behaviours related to a category established? In doing so, “the correct category as status would be an incidental outcome of the behaviours in question” (2022, 36). To answer the behavioural question, Sen draws on Francesco Guala’s characterization of institutions as rules-in-equilibrium. Guala’s work explains the aspects of institutions that normatively guide behaviours and incentivize their being followed. To demonstrate that institutions are rules and equilibria, Guala employs the concept of ‘correlated equilibrium’, which is equilibrium, where no one would be better off by deviating alone, based on external signals observed by those involved.

To explain artwork categorization in these terms, Sen assumes that (1) each critic “has an incentive to categorize an artwork in a way that deepens one’s understanding of the work” (2022, 38) and (2) each critic has an incentive to choose the same categorization as others “because working together to criticize a work based on a particular category helps discover meanings and values that one would not notice on their own” (2022, 38). As Sen highlights, while coordination can be easily achieved with a new work that can be assigned to a salient, socially well-established category, this is not so easy with pioneering works, which call for pioneering ways of appreciation. To describe the origin of a category, Sen proposes two phases: the ‘institutionalizing phase’, where critics “attempt various appreciative behaviours” (2022, 39) and the ‘institutionalized phase’ where a certain “strategy is established as the correct appreciative behaviour for the artwork” (2022, 39). By conceiving of correct categories as institutional outputs, Sen proposes that we can account for the stability of categories in addition to the possibilities and difficulties of critical innovation: when institutions are revised this may have been prompted by unusual appreciative behaviours; appreciators need not rely on linguistic abilities to evaluate a work if they recognize what to do; and while the correct meaning and value of an artwork are relative to its history and community of reception, the correct categories are contingent.

Importantly, with this shift in focus, Sen’s work provides a useful framework for addressing questions about whether the appreciative behaviours related to a particular category are appropriate and even ethical. As history shows us, sometimes the ‘correct’ appreciative behaviours developed towards certain kinds of works are formed on the basis of widespread misunderstandings and biases about particular practices which ultimately fail to deepen understanding of the works. Take the case of a categorization like ‘primitive art’ that became popular in the early 20th century. As time has made clear, not only did the appreciative behaviours associated with this category fail to produce a deeper understanding of the works, but they also manifested and perpetuated unethical attitudes towards those who made and were associated with the cultures where the works originated from. So, by focusing on addressing the behavioural question, rather than the membership question Sen’s account offers a valuable new perspective on how categories originate and develop so that certain appreciative standards take hold. In particular, it helps to make sense of how works, which retain all their features, may end up being categorized differently over time, as a result of the emergence of a new category.

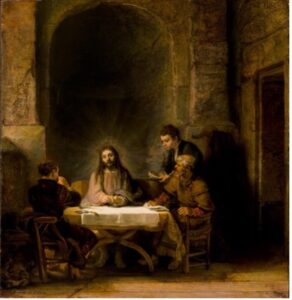

In his article, Verstegen sets out to re-examine the relationship between theories of metaphor by Conceptual Metaphor Theorists (CMT), like George Lakoff, and Gestalt psychologists, such as Rudolf Arnheim. This is prompted by several CMT having appropriated Gestalt arguments from Arnheim. As Verstegen goes to on to explain, this ‘translating’ is not easily sustained. While a Gestalt theory features bidirectionality of topic and vehicle of metaphors, CMT features unidirectionality from target to source. That is because for proponents of CMT, expressive language is based on bodily knowledge, which is formed by lived experience (2022, 46). The conceptual significance of expressions like ‘things are looking up’ is borrowed from some aspect of experience relating to space, time, or movement (2022, 47). Metaphors thus reference conceptual schemas, such as GOOD IS UP, based on experience, which, despite stylistic and semantic differences, they can share (2022, 47-48). Such schemas have been used to translate the work of Gestalt theorists. Lakoff, as Verstegen recounts, re-examined Arnheim’s analysis of Rembrandt’s painting Christ at Emmaus, which “in line with the interactive and creative nature of metaphor” kept “the uncertainty of the units of analysis to painting alive” (2022, 53).

Accordingly, in Rembrandt’s painting, for Arnheim the humility of the apostle and the aggrandizement of the servant is directly seen via the phenomenal tension of the two figures within the compositional framework, while for Lakoff, first we need to observe how the scene is structured by and schemas and infer via interpretation which cultural metaphors are being used (2022, 56). Verstegen highlights the lack of fit between these approaches, noting how Lakoff’s results in stock responses that could be prompted by any number of similarly configured compositions. Indeed, as he outlines, for Gestalt theorists, “meaning is embodied by forms in their chosen medium” while for proponents of CMT, “meaning is embodied in sensorimotor experience” (2022, 54). In relation to visual media, for the former, vision is primary and dominates while the body is secondary, but for the latter, “the sensorimotor experiences passively (through inference) dominate over the visual” (2022, 55). As Verstegen concludes, for Arnheim concepts are perceptual, while for Lakoff, perception is more conceptual.

Verstegen’s article helpfully highlights the tensions between these different approaches and clarifies how, despite the attempts of theorists like Lakoff, the analysis of paintings by Gestalt psychologists like Arnheim cannot easily be accommodated by CMT without loss of appreciation for the metaphorical content as particular to the work, or as interactive and creative. As Verstegen indicates, such appropriations serve to provide further support for Arnheim’s more complex approach and his psychology of art. Nonetheless, from an appreciative perspective we might wonder whether there is some benefit to interpreting certain works through stable cultural metaphors. If, as Arnheim suggested, abstracted qualities from the topic and vehicle “continue to draw life blood from the reality contexts in which they are presented” (quoted in Verstegen 2022, 49) then might it not be the case that, if some reality contexts change over time (particularly if they pertain to cultural phenomena for example), works can take on metaphorical meanings not intended by their creators? If perception is penetrable in the way Arnheim’s account suggests, then viewers may not help but be able to see a work as having metaphorical content that its creator could not have. This might even simply depend on one’s cultural background. Depending upon how much one is sympathetic to actual intentionalism, this may somewhat detract from the attractiveness of Arnheim’s approach. It would thus be fascinating to see how these psychological approaches, or combined aspects of these approaches, work in relation to theories in philosophical aesthetics.

We then have an interview with Ralph Webb, whose collection of poetry Rotten Days in Late Summer (2021) was a Book of the Year for both the Telegraph and the Irish Times, was shortlisted for the Forward Prize, and has received many glowing reviews. In an intimate and honest discussion with Rebecca Wallbank, Ralph Webb talks about what it means to be a writer and we are offered a privileged insight into the poet’s personal process. Wallbank’s well-considered questions lead Webb to reflect deeply on the relationships between a poem, its writer, and its readers; this stimulates the question of why and how poetry moves people, as well as touching on philosophical questions about authorial intention, ownership, and appropriation. In particular, the concept of poetic appropriation, in which a reader takes on the poet’s words as they apply to their own experiences or emotions, is given insightful consideration in this interview and Wallbank remarks upon the surprising degree of interpretive freedom that Webb is happy to allow his readers (2022, 67). She concludes that while a poem or artwork “is not ours to take”, the reader may still “bring something of themselves” to their appreciation of it (2022, 68).

Finally, this issue offers a review of Emmanuel Alloa’s book Looking Through Images: Α Phenomenology of Visual Media by Fotini Charalabidou. Charalabidou concisely and methodically summarises Alloa’s insights on the human experience of images before offering some considered critique regarding Alloa’s underlying assumptions – though she emphasises that, ultimately, this book makes an impressive and noteworthy contribution to the study of mediality (2022, 77).

THE DREAMWORK OF LANGUAGE: DONALD DAVIDSON BETWEEN METAPHOR AND MEANING

Alessandro Cavazzana

↑ Back to top ↑

Davidson’s insights into metaphor are often treated as an isolated episode, with little regard for his work on semantics. In this paper, I want to reassess What Metaphors Mean (1978) in the light of Davidson’s theory of meaning to explain why he is convinced that a metaphor lacks cognitive content and is devoid of any meaning other than that conveyed by its words in their literal interpretation.

1 Introduction

Donald Davidson’s position on metaphors’ cognitive content can be summarised as follows: metaphors are devoid of any cognitive content in addition to the literal (Davidson 1978, 32).[1] The main goal of this paper is to try to reconstruct, step by step, the argumentation that leads to this conclusion, mainly by contextualizing Davidson’s insights into metaphor in the light of his semantics. This contextualization will help to make Davidson’s point about metaphor more plausible, because it will allow for a better understanding of his argument.

Davidson’s What Metaphors Mean (1978) – often treated as an isolated episode and consequently commented on, and criticized with, little regard for Davidson’s work on semantics – hides a very precise theoretical premiss.[2] In this essay, in fact, Davidson discreetly alludes to the theory of meaning to which he refers, and of which he himself was one of the main exponents (Fogelin 1988, 52). This can be seen in some passages scattered throughout the paper, such as:

Literal meaning and literal truth conditions can be assigned to words and sentences apart from particular contexts of use. This is why adverting to them has genuine explanatory power (for metaphors) (Davidson 1978, 33).

According to Davidson (1978), it is important to distinguish meaning from use, that is, the semantic aspect from the pragmatic aspect.

My disagreement is with the explanation of how metaphor works its wonders. To anticipate: I depend on the distinction between what words mean and what they are used to do (Davidson 1978, 33).

Davidson specifies below the type of usage that he considers suitable for metaphorical sentences: “I think metaphor belongs exclusively to the domain of use [as] it is something brought off by the imaginative employment of words and sentences” (Davidson 1978, 33).

Davidson’s assumption, then, is that one should not postulate a metaphorical meaning, since metaphors lack one. Instead, one must evaluate them exclusively in the context of their use, i.e. according to the conditions under which they were uttered or written. Davidson is also convinced that “metaphors mean what the words, in their most literal interpretation, mean, and nothing more” (Davidson 1978, 32). But what does this remark exactly mean?

It is clear that Davidson’s position revolves around the verb ‘to mean’. I, therefore, think that it is necessary to contextualize – and not isolate – What Metaphors Mean (1978) in the light of Davidson’s programme about what form a theory of meaning should take.

2 Meaning and truth

According to the ‘narrow’ account,[3] a theory of meaning must be able to explain what it means for an utterance of a language L to be endowed with meaning (Picardi 1999, 13). Let us see, then, the particular declination that this theory assumes within the Davidsonian proposal, where the notions of interpretation, meaning and truth are intimately connected. In what way? During a linguistic communication, the interpreter assigns truth conditions to the utterances produced by the speaker: according to the truth-conditional semantics, giving the conditions under which a sentence would be true is a way of indicating the meaning of that sentence (Davidson 1967, 310).

Davidson develops a theory that he calls radical interpretation, since, according to the American philosopher; “[t]he problem of interpretation is domestic as well as foreign […]. All understanding of the speech of another involves radical interpretation” (Davidson 1973, 313). The question Davidson seeks to answer is: what kind of knowledge must an interpreter possess in order to assign a meaning to each sentence that is uttered by a speaker? If establishing the truth conditions of an utterance is a way of determining its meaning, then what is needed is a theory of truth; i.e. a theory that can answer the question ‘what is truth?’, or ‘what does an utterance need to possess the quality of being true?’. Davidson’s (1967, 309) first move is, therefore, to replace the schema:

(T) the sentence e means that p

With the equivalence scheme:

(T1) the sentence e is true if and only if p.

The problem with the connective ‘means that’ concerns the “anxiety that we are enmeshed in the intensional” (Davidson 1967, 309). Such a scheme, in fact, does not respond to the Leibnizian principle of substitution salva veritate, since it allows the use of terms that have the same extension but differ in intension. For example, the term ‘red’ and ‘the colour of the Chinese flag’ have the same extension, i.e. red. However, let us consider the following sentence:

(T) ‘red is a primary colour’ means that the colour of the Chinese flag is a primary colour.

It is false because it is not true that the remark ‘the colour of the Chinese flag is a primary colour’ provides the meaning of ‘red is a primary colour’ (De Caro 1998, 22).

Here, Davidson calls into question the theses of the Polish logician Alfred Tarski. Tarski’s aim is to construct a theory of truth that: (a) is based on the idea that the truth of a sentence depends on its correspondence with reality, (b) does not apply only to certain sentences, (c) is rigorous and therefore scientifically respectable (Caputo 2015, 81). With regard to point (a), the truth-world correspondence can be summarised by the expression ‘a sentence is true if it designates a subsistent state of affairs’ i.e. if things in the world are actually the way an utterance says they are. However, such expression, is not considered by Tarski to be a satisfactory definition of truth (Tarski 1944, 343). It is much better, then, the following biconditional (Tarski 1944, 344):

(T1) “e” is true if and only if p.

Where does (T1) come from? Tarski asks us to consider a sentence, for example p, and to give a name to this sentence, for example ‘e’. From the point of view of truth conditions, it is clear that ‘e’ and p are equivalent, since ‘e’ is true only if the conditions described by p are fulfilled; e.g. ‘the grass is green’ is true if and only if the grass has a greenish colour. Moreover, according to Tarski, if the appropriate biconditional is provided for each sentence of a language (L), then each biconditional will constitute only a partial definition of truth. Thus, a general definition of truth for a language (L) will be composed of the logical conjunction of all conceivable biconditionals for the sentences of that language (Tarski 1944, 344). The sentences to be inserted in the place of ‘e’ are not true or false per se, but according to the meaning they have in a given language (L). Thus, the scheme (T1) should be relativised by means of the predicate “true-in-L”, where L indicates the language for which the sentence has a truth value (Caputo 2015, 85). The biconditional thus gains the following form, which is the scheme of the so-called Tarskian Convention T (where, as it is well-known, ‘T’ stands for ‘truth’):

(T1) “e” is true-in-L if and only if p.

Moreover, according to Tarski (1944), to avoid the problems caused by semantic paradoxes, such as the antinomy of the liar, it is necessary to construct the biconditionals using sentences that belong to a semantically open language.[4] A language that is semantically open is one in which there is not the predicate ‘true’ (or ‘true-in-L’). The truth predicate must, therefore, be found outside the so-called object language, which is the one we are talking about and to which ‘e’ belongs. It will be the task of the metalanguage, i.e. the language in whose terms we want to construct the definition of truth for the object language, to host the term ‘true’. Which languages lend themselves to the formulation of a definition of truth? That is, which languages are semantically open? Tarski is convinced that it is not possible to construct a definition of truth for natural languages such as Italian or English because of the risk of running into semantic paradoxes, e.g. the liar paradox. The most suitable languages are, therefore, formalized languages like the ones of mathematics, logic, set theory, and so on (Tarski 1944, 348-351).

Let us come back to Davidson, who directly built his work upon Tarski’s. According to Davidson (1967), if providing the truth conditions of a sentence is a way of indicating the meaning of that sentence, then a theory such as the one elaborated by Tarski can represent an excellent model for a theory of meaning applicable to a given language. In this way, an interlocutor, or reader, will be able to use Tarski’s biconditionals to interpret the speaker’s utterances. Evidently, Davidson does not think that the theory applies only to formal languages but is convinced that the biconditionals can also be constructed with sentences from the natural languages (Davidson 1967, 313). He admits that natural languages are endowed with indexicals, such as verb tenses or demonstrative pronouns; i.e. those parts of the sentence whose truth value varies according to the context in which the sentence is uttered. He, therefore, suggests modifying the biconditionals by adding references to time and the speaker (Davidson 1973, 322). The resulting scheme is:

(T1) “e” is true-in-L when spoken by x at time t if and only if p near x at t.

Davidson assumes a situation where the speaker and the interpreter express themselves in two different languages and where the interpreter does not know the speaker’s language. For example, Kurt – a German speaker – utters the words ‘Es regnet’. The radical interpreter does not know German, but his first move must involve the so-called Davidsonian Principle of Charity (Davidson 1967, 1974), i.e. the interpreter must attribute true and consistent beliefs to Kurt whenever it is permissible, since someone is much more likely to believe things he considers true than those he sees as false (Perissinotto 2002). Moreover, according to the Principle of Charity (Davidson 1967), these beliefs cannot be too dissimilar from those of the interpreter since communication can only take place on the basis of a massive agreement between the two parties. The interpreter must, therefore, believe that Kurt believes that ‘Es regnet’ is true. In that case, the evidence available to the interpreter is also of an extra-linguistic nature and includes, for example, the directly observable behaviour of the speaker, or the environmental conditions, within which such utterances are expressed. The collection and analysis of such data will help the interpreter formulate conjectures about what the speaker is saying but will not be explicitly exhibited by the so-called T-sentences (i.e. the sentences of the form ‘e’ is true-in-L if and only if p). In fact, the right side of the biconditional will merely show the appropriate circumstances under which a speaker expresses the utterance, i.e. the supposed truth conditions for ‘e’ (Picardi 1992, 248-249). Davidson, for example, assumes that the available evidence for interpreting Kurt’s utterance ‘Es regnet’, is Kurt’s membership to the German speech community, the fact that Kurt believes ‘Es regnet’ to be true at noon on Saturday, and that it is raining near Kurt at that time and on that day. The appropriate biconditional will have the following form:

(T1) ‘Es regnet’ is true in German, when spoken by Kurt at noon on Saturday if and only if it is raining near Kurt at noon on Saturday.

Davidson acknowledges that Kurt may be mistaken about the fact that it is raining in his proximity, but the intention is to create a theory that maximizes the agreement between speaker and interpreter, with the speaker being as much in the right as possible (Davidson 1973, 323).

3 Limits of the literal

Is it possible, then, to obtain a truth-conditional theory of meaning for all the utterances of a language? Although Davidson states that he wants to do everything possible to dispel Tarski’s pessimism towards the establishment of a theory for non-formalized languages (Davidson 1967, 313), he admits that there are limits. The metaphor represents one of these limitations. From a truth-conditional point of view, a metaphorical sentence is always patently false or true in such an unquestionable way that the interpreter may find identifying its truth conditions superfluous, thus focusing not on the literal meaning but on the speaker’s intended meaning. When Davidson claims that “metaphors mean what the words, in their most literal interpretation, mean, and nothing more” (Davidson 1978, 32), he is alluding to what I have tried to summarise, i.e. metaphors, as sentences of a language, can be treated like any other sentence and put within a T-sentence, but such an operation is almost worthless since, from a literal point of view, no condition can satisfy the truth of what lies to the left side of the biconditional.

In What Metaphors Mean (1978), Davidson rejects some of the main theses advanced by Max Black (1955) in the context of his interactionist account of metaphor. Contrarily to Black, Davidson does not admit: (i) that the metaphorizing term – the focus, in Black’s terminology – is endowed with a special metaphorical meaning (which is in addition to the literal meaning); (ii) that metaphors have a cognitive content that can be true despite the obvious falsehood of the literal meaning; (iii) that the reason why metaphors cannot be paraphrased lies in their being carriers of another meaning, beyond the normal, literal meaning (Leddy 1983, 64). For what concerns (i), Davidson specifies that what the metaphor conveys to a possible interpreter “depends entirely on the ordinary meanings of those words and hence on the ordinary meanings of the sentences they comprise.” (Davidson 1978, 33). This account fits perfectly into his semantic theory and, indeed, in Truth and Meaning (1967), where he recalls the principles of compositionality and contextuality and states that:

we decided a while back not to assume that parts of sentences have meanings except in the ontologically neutral sense of making a systematic contribution to the meaning of the sentences in which they occur. […]Sentences depend for their meaning on their structure, […] Frege said that only in the context of a sentence does a word have meaning (Davidson 1967, 308).

Basically, the meanings of sentences depend on the meanings of the words that compose them, but it is only in their context that a word acquires meaning. This circularity is also expressed in Davidson’s treatment of metaphors. If at the level of the single word, the only possible meaning is the ordinary, literal one, then this meaning will also be conveyed in the whole sentence, and vice versa. In Max Black’s famous metaphor ‘man is a wolf’, ‘wolf’ is the focus of the metaphor (Black 1955). The system of clichés associated with ‘wolf’ and also valid for ‘man’ suggests that a possible secondary meaning for ‘wolf’ is ‘predatory animal’. Thus the double meaning theory, contested by Davidson, considers “the key word (or words) in a metaphor as having two different kinds of meaning at once, a literal and a figurative meaning” (Davidson 1978, 35). However, in Davidson’s semantic account, the double meaning is not permissible. Davidson’s extensionalism stipulates that the reference of ‘wolf’ is the animal, for which the name stands, and not a connotative description (i.e. an intension) of it since, as we have seen, the instruments adopted by Davidson to indicate the truth conditions of an utterance are constructed with the declared aim of curbing intensionality. Thus, if intensionality is to be contained in a sentence, it is clear that, by the principle of compositionality, this must be done starting from the individual words. That is to say that, in order to avoid intensionality, the meaning of words has to be limited to the ordinary one.

While keeping the metaphor at the centre of our discourse, we now turn our attention to the purpose of Davidson’s theory of meaning, namely, the possibility of interpreting the speaker’s utterances. Earlier, it was said that the interpreter’s first move is governed by the Principle of Charity (1974), according to which the interpreter must take the speaker’s utterances to be true. Metaphor overturns this practice since it works when it is considered to be false. Davidson himself suggests that “is only when a sentence is taken to be false that we accept it as a metaphor and start to hunt out the hidden implication” (Davidson 1978, 42). The metaphor is false in such a bizarre way (or true in such a trivial way) that the interpreter cannot conceive it as a source of information from a strictly literal point of view, nor can she attribute to the speaker the paradoxical belief for which the metaphor stands. This ‘irrelevance’ (or non-relevance) of the metaphor (Sperber and Wilson 1986) will then lead the listener to question the real purpose of such an absurd utterance.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, what the T-sentence succeeds in grasping and evaluating concerns the literal meaning of the metaphor – which is the only kind of meaning Davidson is interested in – and this is exactly what Davidsonian semantics aims at analyzing. It cannot deal with what some critics have called the ‘metaphorical meaning’, since, by Davidson’s own admission, this meaning, if it exists at all, lacks an enunciative form. Through a use of words that involves an imaginative capacity on the part of the interpreter (but also of the speaker), metaphor provokes in the listener or reader a vision, allows for creative elaboration of thoughts, evokes particular connections (Davidson 1978, 47). What a metaphor points out to an interpreter has an extra-linguistic nature that is not verbally delimitable:

there is no limit to what a metaphor calls to our attention, and much of what we are caused to notice is not propositional in character. When we try to say what a metaphor ‘means’, we soon realize there is no end to what we want to mention (Davidson 1978, 46).

Essentially, all that a metaphor makes us imagine is external and does not match any further semantic dimension of the metaphorical sentence.

Finally, this brings us to point (ii). Davidson does not deny tout court that a metaphor has a cognitive content, but he denies that it has additional cognitive content to its literal meaning. Here, Davidson’s implicit assumption is that only sentences are vehicles of such content.[5] If what a metaphor brings to the interpreter’s attention is not reducible to a propositional form, then Davidson also rules out the possibility of further cognitive content in addition to the literal.

At this point, one could ask why Davidson did not formulate his theory of metaphor more explicitly and closely related to his theory of meaning. The answer is contained in this sentence: “I think metaphor belongs exclusively to the domain of use. It is something brought off by the imaginative employment of words and sentences” (Davidson 1978, 33).

Davidson is not formulating any theory of metaphor. He is trying to say that, if the solution of scholars is to postulate a metaphorical meaning, then this particular kind of meaning does not fall into the realm of semantics and, if it does not fall into that realm, it is not something that can be examined with his theory of meaning. In this respect, Davidson is absolutely right, and what I wanted to show here is that his position on metaphors is perfectly consistent with his semantics.

Nevertheless, Davidson offers some alternatives to truth-conditional semantics. He puts on the table some arguments against metaphorical meanings that do not rely on his semantic theory. For example, postulating a new or extended meaning makes it difficult to explain in what way the metaphorical interpretation starts from the original (or literal) meaning (Davidson 1978, 34). Another point against metaphorical meanings lies in the existence of the so-called dead metaphors: if a new meaning has totally replaced the literal one, it is not so simple to say why we no longer consider dead metaphors as metaphors (Davidson 1978, 37-8). Davidson here wants to show that the arguments supporting the existence of metaphorical meanings are weak even when analysed with approaches other than that of truth-conditional semantics.

One of the suggestions offered by Davidson is to compare metaphors to pictures:

How many facts or propositions are conveyed by a photograph? None, an infinity, or one great, unstatable fact? Bad question. A picture is not worth a thousand words, or any other number. […] What we notice or see is not, in general, propositional in character (Davidson 1978, 47).

For Davidson, the working mechanism of a metaphor is comparable to the Wittgensteinian seeing-as; we do not see that Juliet is the Sun, but rather we see Juliet as the Sun. Metaphors make us see one thing as another through a certain literal statement that stimulates an imaginative insight (Davidson 1978, 47). This is also the reason why, for Davidson (1978, 32), metaphors cannot be paraphrased (point iii): the mental images they provoke are not verbally translatable.

This last suggestion, about imaginative insight, has been fruitfully picked up and developed in the field of both visual (Carroll 1994)[6] and verbal metaphors (Carston 2010; 2018).

In the end, Davidson’s great merit was to heavily influence and direct the debate on metaphor, wrenching it away from semantics and fruitfully delivering it to the fields of pragmatics and cognitive linguistics.[7]

References

Black, Max, ‘Metaphor’, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society (1955) 55, 273-94.

Black, Max, ‘How Metaphors Work: A Reply to Donald Davidson’, Critical Inquiry (1979) 6:1, 131-43.

Caputo, Stefano, Verità (Roma: Laterza, 2015).

Carroll, Noël, ‘Visual metaphor’, in Jaakko Hintikka (ed.), Aspects of Metaphor (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1994), 189-218.

Carston, Robyn, ‘Metaphor: Ad Hoc Concepts, Literal Meaning and Mental Images’, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society (2010) 110, 295-321.

Carston, Robyn, ‘Figurative Language, Mental Imagery, and Pragmatics’, Metaphor and Symbol (2018) 33:3, 198-217.

Cavazzana, Alessandro, ‘Immagini (per l)e Parole. La Metafora Visiva tra Occhio Innocente e Immaginazione’, Rivista Italiana di Filosofia del Linguaggio (2017) 11:2, 109-22.

Cavazzana, Alessandro, ‘Imagining: The Role of Mental Imagery in the Interpretation of Visual Metaphors’, in András Benedek and Kristóf Nyíri (eds.), Perspectives on Visual Learning, vol. 3: Image and Metaphor in the New Century (Budapest: Hungarian Academy of Sciences/Budapest University of Technology and Economics, 2019), 71-82.

Cavazzana, Alessandro, and Bolognesi, Marianna, ‘Uncanny Resemblance. Words, Pictures, and Conceptual Representations in the Field of Metaphor’, Cognitive Linguistic Studies (2020) 7:1, 31-57.

Davidson, Donald, ‘Truth and Meaning’, Synthese (1967) 17:3, 304-23.

Davidson, Donald, ‘Radical Interpretation’, Dialectica (1973) 27:3-4, 313-28.

Davidson, Donald, ‘On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme’, Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association (1974), 47, 5-20.

Davidson, Donald, ‘What Metaphors Mean’, Critical Inquiry (1978) 5, 31-47.

Davies, Stephen, ‘Truth-Values and Metaphors’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (1984) 42:3, 291-302.

De Caro, Mario, Dal punto di vista dell’interprete. La filosofia di Donald Davidson (Roma: Carocci, 1998).

Dummett, Michael, The Logical Basis of Metaphysics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991).

Fogelin, Robert J., Figuratively Speaking (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988).

Gentile, Francesco P., Talking Metaphors. Metaphors and the Philosophy of Language (PhD dissertation, University of Nottingham, 2013).

Goodman, Nelson, ‘Metaphor as Moonlighting’, Critical Inquiry (1979) 6:1, 125-30.

Leddy, Thomas, ‘Davidson’s Rejection of Metaphorical Meaning’, Philosophy and Rhetoric, (1983) 16:2, 63-78.

Lepore, Ernest, and Stone, Matthew, ‘Against Metaphorical Meaning’, Topoi (2010) 29:2, 165-80.

Levinson, Jerrold, ‘Who’s Afraid of A Paraphrase?’, Theoria (2001) 67:1, 7-23.

McGonigal, Andrew, ‘Davidson, Metaphor and Error Theory’, in Kathleen Stock and Katherine Thomson-Jones (eds.), New Waves in Aesthetics (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 58-83.

Moran, Richard, ‘Seeing and Believing: Metaphor, Image and Force’, Critical Inquiry (1989) 16:1, 87-112.

Perissinotto, Luigi, Le vie dell’interpretazione nella filosofia contemporanea (Roma-Bari: Laterza, 2002).

Picardi, Eva, Linguaggio e analisi filosofica. Elementi di filosofia del linguaggio (Bologna: Pàtron Editore, 1992).

Picardi, Eva, Le teorie del significato (Roma-Bari: Laterza, 1999).

Reimer, Marga, ‘Davidson on Metaphor’, Midwest Studies in Philosophy (2001) 25, 142-55.

Reimer, Marga, and Camp, Elisabeth, ‘Metaphor’, in Ernest Lepore and Barry C. Smith (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Language (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 845-63.

Sperber, Dan, and Wilson, Deirdre, Relevance. Communication and Cognition (Oxford: Blackwell, 1986).

Tarski, Alfred, ‘The Semantic Conception of Truth and the Foundation of Semantics’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research (1944) 4:3, 341-76.

-

Let us consider the metaphor ‘my brother is the black sheep of the family’. According to Davidson, it makes no sense to distinguish – as many other scholars do – a literal meaning (i.e. the patent falsity that a metaphor like this one expresses) and a metaphorical meaning (the intended meaning, i.e. the fact that my brother is considered as different, bad, worthless, etc. by the rest of the family). For Davidson, the metaphorical meaning simply does not exist. Metaphors show us something not by conveying a well-defined propositional content but by triggering our imagination through the ordinary meanings of words and sentences. In Davidson, the parameter of the cognitive content of the metaphor is the core of what some critics have called error theory (McGonigal 2008). According to the error theory of metaphor, metaphorical statements are not meaningless but literally false. McGonigal tries to defend the following position: “if a sentence used metaphorically is true or false in the ordinary sense, then it is clear that it is usually false. […] most metaphors are false” (Davidson 1978, 41). McGonigal’s polemical target is the radical alethic pluralism defended by Crispin Wright (McGonigal 2008, 76-80). Davidson’s non-cognitivist position is also called causal theory, since a metaphor causes a vision “[making] us attend to some likeness, often a novel or surprising likeness, between two or more things” (Davidson 1978, 33). For a general framing of Davidson’s theory in the analytical debate on metaphor, see Reimer and Camp (2006, 854-8). ↑

-

It is worth summarizing some of Davidson’s critics to show that his insights about metaphorical meaning have almost never been framed within his semantic theory. Max Black (1979), for example, defends his own interactionist account of metaphor against Davidson’s criticism, but his apologia never really contextualizes the sense of ‘meaning’ as understood by Davidson. According to Nelson Goodman (1979), instead, metaphor operates through a mechanism of label application: contrarily to Davidson, he believes that a term is taken from its literal use and applied in a novel way to a new object. Among Davidson’s critics, Richard Moran (1989) disagrees that the message of a metaphor is difficult to delimit from a verbal point of view. For Moran, grasping the meaning of a metaphor means instead selectively limiting interpretation to the right similarities. Jerrold Levinson (2001) replies to Davidson by comparing metaphors to exclamations: like exclamations, metaphors have meanings in context that go beyond the meanings of their constituent words. This further meaning is partly propositional and non-propositional and can, therefore, be paraphrased. The non-propositional part, characterized by an illocutionary force, can still be described (Levinson 2001). Stephen Davies (1984), on the other hand, largely adheres to Davidson’s position, arguing that the truth value of metaphors is linked to their literal meaning, which is the only meaning metaphorical utterances have. Among those inspired by Davidson, at least in terms of their denial of metaphorical meaning and metaphorical truth, see also Lepore and Stone (2010). With other methods and other purposes besides those of this paper, the only work which attempted to contextualise Davidson’s insights on metaphor in light of his theory of meaning was Gentile’s PhD dissertation (2013). ↑

-

For Michael Dummett there is a meaning-theory and the theory of meaning. The former is specific to a specific language: “[it] is a complete specification of the meanings of all words and expressions of one particular language” (Dummett 1991, 22). While the latter has to define what general principles are needed to build the former. The task of the theory of meaning, according to Dummett, is to provide an explanation of how language works, i.e. to explain what happens when a speaker utters a sentence (in a certain language) in the presence of a competent listener (Dummett 1991, 21). ↑

-

Tarski (1944) recalls the liar paradox in this way. Consider the sentence “(a) is not true”. Let us give a name to this sentence, calling it (a). The resulting biconditional is as follows: “(a)” is true if and only if (a) is not true. The contradiction is obvious, which is why, according to Tarski, an object language must be semantically open, i.e. it must not contain the predicate “true” (Tarski 1944, 347-348). ↑

-

For a critique of this position see Reimer (2001). Reimer (2001) summarises Davidson’s argument as a modus tollens: [ ( p ” q ) ^ ¬q ] ” ¬p. Where: p = a metaphor has a special cognitive content; q = it is possible to provide this (presumed) content through a literal expression. So, Reimer’s reconstruction of Davidson’s argument sounds like: if a metaphor has a special cognitive content, then it is possible to provide this (presumed) content by means of a literal expression, but it is not possible to provide this (presumed) content by means of a literal expression, so a metaphor does not have a special cognitive content. Reimer disagrees with q; she believes that cognitive content is not the only content that can be expressed verbally (Reimer 2001, 145). ↑

-

For a critical reading of Carroll’s account (1994) of visual metaphors, see Cavazzana (2017). For the importance of imagination in the perception of visual metaphors, see Cavazzana (2019), as well as Cavazzana and Bolognesi (2020). ↑

-

I would like to thank the anonymous referees for their precious comments. ↑

AN INSTITUTIONAL THEORY OF ART CATEGORIES

Kiyohiro Sen

↑ Back to top ↑

It is widely acknowledged that categories play significant roles in the appreciation of artworks. This paper argues that the correct categories of artworks are institutionally established through social processes. Section 1 examines the candidates for determining correct categories and proposes that this question should shift the focus from category membership to appreciative behaviour associated with categories. Section 2 draws on Francesco Guala’s theory of institutions to show that categories of artworks are established as rules-in-equilibrium. Section 3 reviews the explanatory benefits of this institutional theory of the correct category.

Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that categories play significant roles in the appreciation of artworks. Categories affect interpretation: we can assume that the setting of a Western film is the United States during the Wild West, even if that is not stated explicitly in the story. Categories affect evaluation: if it is a musical, we cannot view it as silly when characters suddenly start singing and dancing. Not only genres but other types of categories too — form, style, movement, tradition — can have similar effects[1].

Here, I would like to take categories in a broader, more general, way, that is as points of view, ways of seeing, or frameworks for appreciating artworks. A work of art can, in principle, be perceived from several different categories. For example, we could judge Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) as a mystical and sublime masterpiece as a science fiction film, or we could judge it as a dull and uninspired waste of time as a romance film. However, the latter judgment would miss the point or be less appropriate than the former. Walton (1970) famously argued that there are correct categories for artworks, and the correct appreciation of a work is based on such categories. This raises the question, what determines the correct categories?

This paper argues that the correct categories of artworks are institutionally established through social processes. Section 1 examines the candidates for determining the correct categories and proposes that this question should shift the focus from category membership to appreciative behaviour associated with categories. Section 2 draws on Francesco Guala’s (2016) theory of institutions to show that categories of artworks are established as rules-in-equilibrium. Section 3 reviews the explanatory benefits of this institutional theory of the correct category.

1 The correct category and membership

Walton sketches four factors that “count toward its being correct to perceive a work, W, in a given category, C.” (1970, 357):

(i) “The presence in W of a relatively large number of features standard with respect to C. […] it has a minimum of contra-standard features […] .”

(ii) “W is better, or more interesting or pleasing aesthetically, or more worth experiencing when perceived in C than it is when perceived in alternative ways.”

(iii) “the artist who produced W intended or expected it to be perceived in C, or thought of it as a C.”

(iv) “C is well established in and recognized by the society in which W was produced.” (Walton 1970, 357)

Above all, Walton emphasizes the importance of the criterion (iii), that is, the author’s intention (cf. Walton 1973). The idea that the author’s intention determines the correct categories of a work of art is deep-rooted and held even by those who otherwise prefer non-intentionalist approaches (cf. Levinson 1996, 188-189; Davies 2006, 233).

There are reasons and cases to doubt the intentionalism on categorizations. Categorical intentions are insufficient insofar as categories are frameworks for interpretation and evaluation. Allowing artists to solely determine the category of a work would grant the artist’s intention implausibly strong powers in determining the work’s meaning and value. That is, the artist could set a self-serving bar for her work. It is odd that a work that is only incoherent and sloppy should be interpreted as a symbol of something significant or evaluated positively simply because the artist intended it to be a piece of Absurdist fiction. Moreover, we should consider cases where the author’s intention fails. When the artist attempts to create an artwork that belongs to a given category C, the categorical intention alone is not sufficient for the attempt’s success (cf. Mag Uidhir 2010).

To regard the categorical intention as a necessary condition is too restrictive in the following respects. As it is evident in practice, an artwork often belongs to a category that the author did not intend when it was created. Reading Raymond Carver’s work as minimalist literature or listening to Portishead as trip-hop involves categorizations that the authors did not intend or openly rejected. Moreover, an artwork may belong to a category that the author cannot intend. Reading Kafka’s or Dostoevsky’s works as existentialist literature or watching Tarkovsky’s films as slow cinema involves categorizations established long after the creation of these works. Since such categorizations occur in practice, theoretically dismissing these categories as incorrect would be a cost to pay. I would instead look for a theory of categories that approves various critical practices (cf. Gaut 1993, 605).

The four factors listed by Walton would be helpful as a heuristic for identifying the correct categories. However, none of them seems to provide logically necessary or sufficient conditions for category membership. Moreover, Walton (1970) treated categories as existing options and said little about the origins of categories. For example, how a category is associated with a particular set of features and what it means for a category to become established remains open.

As Walton (1970, 362) acknowledges, tightening up the conditions that determine the correct categories would be difficult. It is also quite possible that different categories have different conditions of membership or different priorities of factors. Therefore, the theory of correct categories needs a different approach. I propose that the question of what determines the correct category of a work (the membership question) should be replaced by how the correct appreciative behaviours related to that category are established (the behavioural question). By centering the behaviour, the question of category membership can be skipped.

As mentioned in the introduction, correct categories have normative roles in appreciation. The fact that a work belongs to a particular category is not just a matter of membership. It is also about undertaking certain appreciative norms. This normative aspect of categories can be described as a combination of the Membership rule and the Status rule.

(M) If X has the property F, then the correct category of X is Y.[2]

(S) If the correct category of X is Y, then the one who appreciates X should Z.

Z will be filled with a particular set of appreciative behaviours associated with category Y. If the work belongs to a specific category, one would be granted to assume that the setting is the United States or prohibited from evaluating it as silly just because characters start singing and dancing. This is analogous to the case of money: if X has specific historical and physical property F, X is money (Y), and if it is money, X is accompanied with rights and obligations concerning a set of economic behaviours (Z).

Here, importantly, the two rules above can be converted into a more straightforward norm of behaviour (Guala 2016, chap.5). Namely, a Regulative rule.

(R) If X has the property F, then the one who appreciates X should Z.

Here, the problem of membership to the correct category is skipped, transformed into a problem about appreciative behaviours. Then the correct category as status would be an incidental outcome of the behaviours in question.

Thus, the explanatory buck is passed to how the regulative rules under each correct category arise and become established. I am going to argue that the theory of institutions explains it.

2 Categories and institutions

Francesco Guala, in Understanding Institutions (2016), characterizes institutions as rules-in-equilibrium. By integrating the rule theories and equilibrium theories of institutions, Guala’s approach compensates for the shortcomings of each. If institutions are rules, we can explain the aspects that normatively guide behaviours. However, if they are merely rules, and not equilibria, the difference between followed institutions and those that are not is unclear. If institutions are equilibria, we can understand whether they are followed by seeing whether there are enough incentives. However, if they are merely equilibria, and not rules, we cannot explain the aspects that guide behaviours. Guala employs the concept of correlated equilibrium in coordination games to show that institutions are rules and equilibria.

In a practical sense, it does not matter whether a traffic law requires driving on the right or the left. What matters is to avoid the situation in which each driver chooses their lane freely and creates chaos. An agreement like driving on the right side in this country solves this coordination game. In this case, the strategy of following the agreement together (the “correlated” strategy) becomes the equilibrium of the situation in that no one would be better off by deviating alone. That is why people follow the agreement. A correlated equilibrium is an equilibrium based on external signals that are observed by each player. In this case, the signal is the public agreement. Additionally, driving as it has been agreed becomes a normative rule for each driver, or “player”, to follow. The rule guides behaviours, and whoever violates it receives penalties imposed for interfering with the traffic flow. Penalties reduce the incentive to deviate and reinforce normativity. In this way, certain behaviours are maintained within a society. According to Guala, institutions are rules-in-equilibrium.

Correlated equilibrium can also be applied to cases with asymmetric payoffs. Suppose that when a couple decides where to go on a date. Player 1 wants to go to A, while Player 2 wants to go to B. At the same time, however, neither of them wants to choose selfishly to give up their date. Figure 1 is the payoff matrix for this case, and each cell shows Player 1’s payoff on the left and Player 2’s payoff on the right. In this situation, for example, the agreement of deciding where to go by tossing a coin can be a signal of coordination. Suppose the probability of getting heads or tails is one in two for each, and they will go to A for a head and B for a tail. Participating in the coin toss can be a correlated equilibrium because deviating and going where they want to go on their own would not bring a bigger payoff. It is also desirable in terms of equality.

Figure 1. Correlated equilibrium for games with asymmetric payoffs

How is the artwork categorization game played? Let us assume two things. Firstly, each critic has an incentive to categorize an artwork in a way that deepens one’s understanding of the work, that is, in a way one prefers. This is not an assumption that all critics seek to maximize the value of a work. The category that helps me notice a work’s severe flaws and points out how it fails to achieve its goals is my preferred one because it deepens my understanding of that artwork. Secondly, each critic has an incentive to choose the same categorization as other critics because working together to criticize a work based on a particular category helps discover meanings and values that one would not notice on their own.[3] These assumptions lead to a situation that is analogous to the couple deciding where to go on a date, i.e. an asymmetric coordination problem.[4]

If the work to be appreciated is a typical one, coordination will be easy to achieve thanks to precedent works (Xhignesse 2020, 479).[5] It is not difficult to assign a new work to salient, socially well-established categories, in which the connection between standard/variable/contra-standard features and the categories is solid. There is no difficulty in categorizing Christopher Nolan’s Tenet (2020) as a science fiction and action film. The real problem occurs when pioneering works require pioneering ways of appreciation. According to Xhignesse, “their existence calls for a theory of the art-kind which they pioneer, […] they call for the development of conventions” (2020, 474). Works such as Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), Alejo Carpentier’s The Kingdom of This World (1949), Herschell Gordon Lewis’s Blood Feast (1963), and The Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight (1979) require more than just putting them into existing categories at the time of their creation. It is not difficult to imagine that categories that are well established today also had pioneering works that called for the new categories at the beginning of their history.

As we saw in the previous Section, the choice of categories can be converted into the choice of appreciative behaviours. With this in mind, the origin of a category can be described in two phases. In the institutionalizing phase, critics attempt various appreciative behaviours. As mentioned above, critics, who confront each other, have incentives for both their preferences and agreements. Over a pioneering work, some prefer to Z1; while others prefer to Z2. Here, the critics should be taken in a broad sense. The theoretician-inclined artists would often be the first critics of their works, promoting specific behaviours. Categories like Nouvelle Vague and the Readymade were thus theoretically driven by the artists. In the institutionalized phase, a particular strategy is established as the correct appreciative behaviour for the artwork: collectively choosing that behaviour becomes a rule-in-equilibrium.

Meanwhile, the categories behind these appreciative norms were named conceptual art, magic realism, splatter film, or rap music. It helps us solve coordination problems smoothly based on precedents when we encounter new works with similar properties. This background is also consistent with what Walton points out as the causes of perceiving works in specific categories (1970, 341-342): (a) our familiarity with other works, (b) categorization by critics and others, and (c) the context in which we encounter the work.

However, suppose the incentive to choose the individually preferred category is much greater than the incentive to choose the same category as other critics. In that case, the correct category might not take hold. If both players prioritize their preferences over an agreement when deciding where to go, the only equilibrium is to give up on their date. The uniqueness of equilibrium remains unchanged even when the game is extended by adding the strategy of participating in a coin toss. Here, the couple is in a so-called prisoner’s dilemma:[6] even though the strategy of participating in the coin toss is superior in terms of payoff, players cannot but act selfishly (Figure 2). If the artwork categorization game has such a payoff setting, then no one needs correct categories.

Figure 2. Prisoner’s dilemma in a selfish couple

There are three possible responses to this supposed objection. Firstly, such a payoff setting is questionable in that it is at odds with the existing practice of critical consensus on the interpretations and evaluations (cf. Walton 1970, footnote 21). It precisely shows the situation where there is no disputing about taste, and it is difficult to recognize the significance of critical debate. Secondly, even if the incentive to choose the individually desirable categorization is great, it is not an immediate threat to establishing correct categories. The correct appreciative behaviour is established in a reflective equilibrium through more detailed negotiation instead of a random coin toss. Even if an inappropriate interpretation or evaluation is made, the features and facts that do not fit it do not disappear. This prompts re-categorization, which eventually leads to a better category by equilibrium. The reached consensus will be superior at least to the expected value of the coin toss as far as the payoff is concerned. Thirdly, Guala (2016, chap.6) shows a path to convert the prisoner’s dilemma into a coordination problem by considering the costs (penalties) associated with breaking the rule. In this regard, there could be institutions that would be useful for prisoner’s dilemma situations too.

3 Explanatory benefits and consequences

One of the advantages of identifying the correct categories as institutional outputs is that we can observe the categories’ stability as well as the critical innovation’s possibilities and difficulties. When a specific categorization of a work is firmly established as a rule-in-equilibrium, the attempts at unusual appreciative behaviours are often weeded out without having much impact. However, in rare cases, they may prompt a revision of the institution. Evolutionary games may explain this. When an evolutionarily stable strategy is given, even if a few new players choose a strange strategy, the stable state is maintained without a proliferation of players choosing such mutable strategies.[7] However, a highly applicable strategy (in our case, a highly attractive categorization) may arise as a small number of mutations and eventually lead to another equilibrium that is superior to the current rule-in-equilibrium.

The advantage of adopting Guala’s account of the institution over other accounts is that it does not require the player to display a high degree of linguistic ability. There is no need to collectively recognize that the category to which a work belongs is called ‘horror’ if one can recognize what to do. We recognize that the purpose of the work is to frighten the viewer, so it should be evaluated according to the effectiveness of the means. We recognize the precedents and conventions, which shape how we interpret that artwork. Like the etiquette of standing on one side when using an escalator, the rule-in-equilibrium does not always have a name. Jan Švankmajer’s works are authentic when seen as a category that evokes disgust through vulgar eating scenes. We do not need the category’s proper name to make such an evaluation. Of course, since having a name is advantageous to the operation and modification of the institution, naming and describing informally accepted categories will be one of the critics’ essential tasks.

If the correct categories are institutional outputs, then the correct meaning and value of a work of art are relative to its history and the community of reception. In this regard, the stable state of a game often has path dependence on its initial conditions. Suppose a situation where a coordination game is being played repeatedly in a group. The strategy chosen by a randomly selected player is influenced by the ratio of strategies in the group: if many people use Windows, I choose Windows; if many people use Macintosh, I choose Macintosh. If the percentage of Windows users is above a certain level, the randomly selected player has more incentive to choose Windows. Eventually, an equilibrium will be achieved where most people choose Windows. The same thing can happen with Macintosh since the achieved equilibrium depends on the initial state at a given point in time. Although there are many other factors to consider in the real world, this is partly how VHS defeated Betamax and Blu-ray defeated HD DVD. Likewise, the categorization of an artwork that was salient in the early days of its publication may affect the correct categories, later established. In this respect, the current correct categories are contingent and, like social institutions, not always the best. Tracing these origins and transitions, and then documenting the facts, will be one of the essential tasks for art history.[8]

References

Abell, Catharine, Fiction: A Philosophical Analysis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Davies, Stephen, ‘Authors’ Intentions, Literary Interpretation, and Literary Value’, British Journal of Aesthetics (2006) 46:3, 223-247.

Gaut, Berys, ‘Interpreting the Arts: The Patchwork Theory’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (1993) 51:4, 597-609.

Guala, Francesco, Understanding Institutions: The Science and Philosophy of Living Together (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

Laetz, Brian, ‘Kendall Walton’s ‘Categories of Art’: A Critical Commentary’, British Journal of Aesthetics (2010) 50:3, 287-306.

Levinson, Jerrold, The Pleasures of Aesthetics: Philosophical Essays (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996).

Mag Uidhir, Christy, ‘Failed-Art and Failed Art-Theory’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy (2010) 88:3, 381-400.

Walton, Kendall, ‘Categories of Art’, Philosophical Review (1970) 79:3, 334-367.

Walton, Kendall, ‘Categories and Intentions: A Reply’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (1973) 32:2, 267-268.

Xhignesse, Michel-Antoine, ‘What Makes a Kind an Art-kind?’, British Journal of Aesthetics (2020) 60:4, 471-88.

-

Inherent categories such as the author, performer, period, region are beyond the scope of this paper. Media understood as a purely physical vehicle should also be set aside in this sense. Here I am concerned with acquired categories that cannot be determined by historical facts alone. A film made by Hitchcock can avoid being a suspense film but cannot help being a Hitchcock film. In this respect, whether it is a Hitchcock-style film is not inherently determined. ↑

-

Here, the property F should not be understood only as perceptual properties of a work. It also includes relational properties, such as being the product of a successful intention or having a causal connection to precedents. Repeatedly, it is hard to find a condition that is determinative for category membership, but the approach of this paper has the advantage of leaving property F open. My approach is compatible with a position like Laetz’s (2010), which is sceptical of equating the correct category with the category to which the work belongs. ↑

-

Abell (2020) identifies ‘the communication of imaginings’ (32) as a coordination game to be solved and argues that the contents of fictional utterances are institutionally determined. Although her interests and assumptions differ from mine, some of my arguments overlap with Abell’s insofar as categories have interpretive roles. ↑

-

Xhignesse (2020, 477-8) is hesitant about my assumption here, and argues that many artistic practices are not like solving a coordination problem. Such remarks do not threaten the argument of this paper because my argument is more limited than his, and I only argue that one of these practices, the critical categorization of works, is a coordination problem. ↑

-

To the question of what makes a given kind an art-kind, Xhignesse (2020) takes an approach like mine, appealing to the existence of social practices. However, while I rely on Guala’s institution, Xhignesse prefers Millikan’s convention as the explanans. ↑

-

There is a dominant but inefficient equilibrium in the prisoner’s dilemma, so it is not a coordination game because the problem of choosing among multiple equilibria does not arise. In the classic example, the choice to remain silent together is efficient but not an equilibrium. ↑

-

Evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) was introduced by John Maynard Smith and George R. Price to explain natural selection. A strategy S is evolutionarily stable in a particular group if and only if every player selects S; selecting alternative strategies would not improve one’s reproductive fitness; that prevents mutant strategies from invading. ↑

-

I would like to thank John O’Dea for helpful discussions. Thanks also to anonymous referees for insightful comments. ↑

IS LAKOFF ARNHEIMIAN?

Ian Verstegen

↑ Back to top ↑

Cognitive psychology has expressed its debts to Gestalt Psychology and Conceptual Metaphor Theorists (CMT) such as George Lakoff have expressed debts to Gestalt psychologists, like Rudolf Arnheim. However, there are prima facie obstacles to this easy genealogy, especially the Gestalt preference for an interaction theory of metaphor. This paper addresses these issues by, firstly, revisiting the discussions of metaphor by Gestalt-oriented psychologists and comparing them to CMT. Secondly, the paper discusses the ways in which CMT has appropriated Gestalt ideas, usually as a ‘translation’, but not a true assimilation. Lastly, the paper focuses on Lakoff’s discussion of a static image using CMT and uses the insights of Gestalt-theoretic critiques of CMT to explain its shortcomings in the visual domain.

Fig. 1, Rembrandt, Supper at Emmaus, 1648, Louvre (Wikimedia: image in public domain)

1 Introduction

Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) has proven to be a highly durable theory of expressive language. It explains expressive language as something based on bodily knowledge, that is formed by lived experience. Cognitive psychology has expressed its debts to Gestalt Psychology and Conceptual Metaphor theorists, such as George Lakoff, have expressed debts to Gestalt psychologists, like Rudolf Arnheim. But how is Gestalt linked to CMT and to what degree is Lakoff ‘Arnheimian?’ In particular, what are we to make of Lakoff’s renderings of spatial analyses of paintings that have been undertaken in the manner of Arnheim in his own language of CMT?

The argument of this paper is that Arnheim’s position is more complex than CMT’s, and should not be regarded as a simple stepping stone towards it. Indeed, there is more work in the domain of contemporary metaphor theory, equally inspired by Gestalt theory, that has developed important critiques that lend further support for Arnheim and his psychology of art. By clarifying Arnheim’s position on metaphor, we can see more clearly some of the simplifications and only apparent improvements that CMT has contributed to metaphor theory.

This paper answers this question through a series of discussions. Firstly, it compares CMT with the Gestalt-Interaction theory of metaphor (Glicksohn 1994; Goodblatt & Glicksohn 2003, 2010) to identify its consistent critiques, which include the need to recognize the bidirectionality of metaphor and the productivity of metaphoric imagery. Secondly, it reviews the appropriations of Arnheim and Gestalt psychology by CMT researchers. Lastly, it extends the critique of CMT by the Gestalt-Interaction theory in the domain of spatial imagery.

2 CMT Versus Gestalt on Metaphor

In traditional metaphor analysis, a metaphor like ‘man is a wolf’ is parsed into its tenor (or topic), ‘man’, and vehicle, that is ‘wolf’, enlivening our sense of man and vice versa. However, CMT is not only set to analyse language but also to argue for the metaphoric structure of experience itself. As an example of Lakoff’s approach to metaphor, the expression ‘things are looking up’ reflects the conceptual schema (known as a cross-domain mapping) ‘GOOD IS UP’. Here, the source domain invariantly maps (verticality) onto the target (value) and borrows conceptual significance from some aspect of experience relating to space, time, or movement.

Not only the conceptual power of the metaphor flows in one direction but also becomes somewhat ‘Kantian’, in the sense that a category is invoked and then becomes the actual meaning. That is, a metaphor would reference a conceptual schema based on experience. In a sense, the conceptual schema is more real than the metaphor because it animates the metaphor through lived experience. Once it is invoked, the metaphor merely effects the mapping of the mind. For this reason, cross-domain mappings can be interpreted as mere ‘stock responses’ (Tsur 2000). For example, ‘things are looking up’ is no different from ‘we’re rising to the top’ because they have the same schema, that is ‘good is up’. However, stylistically and semantically, they are vastly different.

This is a problem for the phenomenology of poetic language. It has always been accepted that metaphor is a literary device that is used to surpass language’s literal semantic repertoire. Arnheim (1966) explained that metaphors make concepts tangible by referring to sensory experience thereby giving the words tangible meaning. But this is different from CMT according to which the body merely serves as an ultimate source of meanings resulting in a sedimented semantics. Similarly, if metaphors direct us to the schematic mapping of experience, this thwarts the creative and expressive elements of metaphors, which are often incongruous and search after new meanings rather than stock responses. Generally, metaphors are dynamic and mutually inflecting. A novel metaphor would not work, not due to a sensed aptness, but merely because the overlaying conceptual schema are relatively similar in structure.

Specialists have pointed out further problems to do with poetic language, which stress the inadequacy of bodily schemas to service all poetic metaphors and, furthermore, the bidirectional mapping of topics and vehicles (Brandt 2013; Goodblatt & Glicksohn 2017). Some of the inadequacies of CMT have given rise to development in ‘blending’ theory, associated with Gilles Fauconnier and others (Fauconnier & Turner 2002). But this development is to bypass the venerable Interaction theory of metaphor, which gave rise to the Gestalt-Interaction theory of metaphor (Glicksohn 1994; Goodblatt & Glicksohn 2003, 2010) based on Gestalt precedents (Asch 1961; Arnheim 1966). Features of a Gestalt theory that are lacking in CMT include bidirectionality of topic and vehicle and, a related problem, a novel outcome of metaphoric signification. CMT has a permanent feature, that is the unidirectionality from target to source of metaphors. For Lakoff (2006, Lakoff & Turner 1989), the metaphor always passes from conceptual to perceptual. In this claim, he explicitly built this theory in contrast with the Interaction theory associated with I. A. Richards (1936), Max Black (1979), and the Gestaltists, for whom there is a back-and-forth movement from topic to vehicle (Goodblatt & Glicksohn 2003, 2010). Lakoff and his collaborators always resisted the Interaction theory of metaphor (Johnson 1987, 69-70; Lakoff & Turner 1989, 131-133).

The poetic element in a metaphor arises from the structural conflict caused by forcing heterogeneous elements or components of reality – that is, tenor and vehicle – into a whole. Unity for this whole is only attained through a retreat to the more abstract level of common expressive qualities. Arnheim writes,

negatively, the reality-character of the components is toned down and…positively, the physiognomic qualities common to the components are vigorously underscored in each. Thus, by their combination, the components are driven to become more abstract; but the abstracted qualities continue to draw life blood from the reality contexts in which they are presented (Arnheim 1966, 279).

A good example is given by Chanita Goodblatt and Joseph Glicksohn (2003); that is, John Donne’s poem The Bait (1633). The conceit is that love is described as fishing. Donne writes of the ‘enamour’d fish’, who will ‘amorously to thee swim’. On a standard reading that is consistent with Lakoff’s approach, the target domain of courtship is made more familiar with the language of fishing; the poetic metaphor must be enriched with the conceptual schema of fish pursuing bait. In this way, “men become suffused with the predatory attributes of carnivorous fish feeding on human bait” (Goodblatt & Glicksohn 2003, 215). However, the opposite also occurs. As indicated by the ‘enamour’d fish’, “fish are suffused with sexual desire” (Goodblatt & Glicksohn 2003, 215). The theme of courtship is not the only thing enriched; our sense of a fish’s behaviour is as well. Indeed, in Goodblatt and Glicksohn’s Gestalt-interaction theory of metaphor (Glicksohn 1994; Goodblatt & Glicksohn 2003, 2010), the process of arriving to a satisfying interpretation of the metaphor is akin to problem solving and far from simply tracing the target back to schema.

In these brief examples, we have seen that there is a long-standing contrast between the Interaction theory of metaphor in its Gestalt guise (Asch 1961; Arnheim 1966) and CMT. Turning to the visual arts, we would expect that the problems of stock responses, bidirectionality and the novelty of metaphors would be relevant in some ways.

3 CMT Appropriations of Gestalt Phenomena